Page 26 (new hotel - La Noce)

Page 27 (people/places 2003)

Page 28 (people/places 2003)

Page 29 (Nino Di Pietrantonio)

Page 30 (people/places 2003)

Page 31 (Anagrafe / Stato Civile)

Page 32 (people/places 2004)

Page 33 (people/places 2004)

Page 34 (people/places 2004)

Page 35 (S. Nicola Church 2005)

Page 36 for future construction

Page 2 (history/photos)

Page 3 (history/photos)

Page 4 (photos)

Page 5 (photos)

Page 6 (photos)

Page 7 (photos: festa)

Page 8 (stone-sculpting)

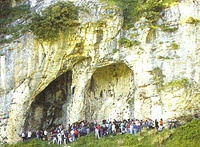

Page 9 (Iconicella)

Page 10 (people/places)

Page 11 (people/places)

Page 12 (festa 2000)

Page 14 (Marcinelle)

Page 15 (people/places 2001)

Page 16 (people/places 2001)

Page 17 (people/places 2001)

Page 18 (people/places 2001)

Page 19 (people/places 2001)

Page 20 (sculpting school)

Page 21 (fonte)

Page 22 (old photos)

Page 23 ( history)

Page 24 (street map)

The present-day town of Lettomanoppello arose during the medieval era, but centuries earlier a Roman settlement existed there. The area is rich in mineral resources, including asphalt, and the Romans developed an asphalt mine in what is now the Valle Romano section of Lettomanoppello, on the mountainside just above the present-day center of the town. The mine was worked by African and Asian slaves, whose cookhouse was located below the mines, in the Fonte Marte section of the present-day town, on the road that now leads from Lettomanoppello to Manoppello. The bitumen or asphalt was mined in large chunks which were transported to Rome via the Aterno River or on the backs of pack animals. It was used primarily to caulk the hulls of Roman ships but had other uses as well.

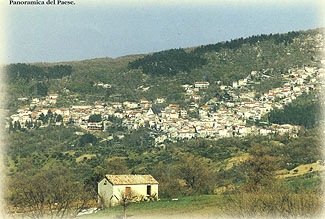

Present-day Lettomanoppello, located at an elevation of about 1200 feet near the base of La Maielletta - one of the Maiella mountains - was born during the medieval era. The earliest written reference to the town dates from the year 1047AD. This reference is found in the Chronicon Casauriense, an historical record of the area kept by the monks of the Abbey of San Clemente a Casauria. The reference to Lettomanoppello notes that in 1047 the village, called in Latin 'Terra lecti propre Manoppellum' (Land of the Letto, owners of Manoppello), was fortified.

Throughout the medieval era and indeed up until the unification of Italy, control of Abruzzo passed back and forth among various European powers, including France, Spain and Austria. In the 1800s Lettomanoppello served a particular function under the Bourbon rulers: it was a penal colony for political prisoners.

Even today, traces of the French influence can be seen in the dialect of Lettomanoppello – because the town was a stone-quarrying and sculpting center, the lettesi had much contact with the French regarding orders for stone and carvings, and French words found their way into the dialect – moi for me, trois for three, for example.

Lettomanoppello is situated in the foothills of the Maiella mountains, an area where the land is steep, rocky, rather arid and infertile – it was not conducive to an economy based on farming. Agriculture was limited to subsistence farming, whereby families provided their own food by raising small crops, frequently on narrow terraced plots painstakingly built with stone on the mountainside. Some of the terracing can still be seen today, particularly on the section of mountainside known as Cerratina, just above the town.

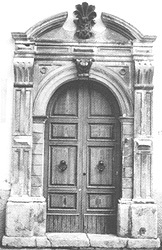

Despite the poverty of the land, the town flourished because of the two industries that resulted from its mineral wealth: asphalt mining, described above, and the quarrying, cutting and sculpting of stone for building and for decoration (see Lu Lette Pg. 8). There are early references to Lettomanoppello’s success as a stone-quarrying and sculpting center: tradition says that in the 7th century a group of Lettesi stonecutters was called to Byzantium (Constantinople) to work on the restoration of several buildings there, including the Santa Sofia, and that in recognition of this work the Lettesi were given an icon of the Virgin Mary, which they venerated ever after. Such an icon did exist at Lettomanoppello, but in 1799 it was destroyed during the French invasion of Abruzzo. (For more about the tradition of the Madonna of the Iconicella, see Lu Lette Pg. 9.)

Records of the 16th century indicate that in the 1500s white stone from Lettomanoppello was being shipped to Egypt.

The peak of Lettomanoppello’s success in stone-quarrying and sculpting was the era from 1800-1900. In the historical archives at Naples is a text dated 1828, which speaks of Lettomanoppello as a place totally devoted to the working of stone, so much so that the town became known as "Piccola Carrara d'Abruzzo" - the little Carrara of Abruzzo.

Fortunately, a nucleus of sculptors has always remained in the town, and the craft of sculpting is in revival; a sculpting school has been established in the town to insure its preservation (See Lu Lette Pg. 20).

While farming in Lettomanoppello was always marginal due to the climate and terrain, the raising of sheep for the cheese that could be made from their milk as well as for their wool was a viable alternative; sheep-raising was a major industry throughout the mountainous interior of Abruzzo for millenia.

The broad pastures of the altopiano, atop the mountain above Lettomanoppello, provided lush summer grazing for the flocks. Signs of this pastoral activity remain today.

In Puglia the shepherds learned the art of building small dry-stone (no mortar) shelters, and they imported this art back to Abruzzo, building the tholi or capanne that can still be seen on the mountainside above Lettomanoppello today, particularly near the locality known as Cerratina. These structures, no longer used, date mainly from the 17th century (although some are much more recent). They are widespread throughout Abruzzo and are a part of the region’s cultural heritage.

Although scalpellini still cut and carve stone in Lettomanoppello, and flocks can still be seen on the altopiano at the top of the mountain above the town, neither stone-work nor sheep-raising is any longer a significant source of work in the town, which today suffers from a lack of employment opportunities for the young. In order to find work, most young people must now commute to the bigger centers, such as Pescara or Chieti, or leave the area altogether.

The worst of economic hard times for Lettomanoppello, as for the rest of Abruzzo, was at the turn of the century (1875 –1925) - during this period 20% of the population of Abruzzo was forced to emigrate to North America, South America, and to other European countries in order to find work and survive. The feudal system, under which our peasant ancestors did not own land but had the use of it under feudal landlords, had been abolished some years earlier. This resulted in the privatization of land, leaving the mass of peasants without access to land on which to grow food for their families. Moreover, the wealthy landowners, eager to create more grazing so that they could raise more sheep, cleared the forests higher and higher on the mountainsides, which resulted in erosion of arable lands below. These and other factors destroyed a lifestyle that had supported the people of the region for millenia, forcing so many to disperse around the world. The new government of Italy had no help to offer, and actively encouraged the emigration. A second exodus occurred after World War II, when unemployment was extreme throughout Italy, especially in the mezzogiorno of which Abruzzo is a part. As a result, today, emigrants and descendents of emigrants from Lettomanoppello can be found all over the world.

Despite the economic hardships of the past and the problems of unemployment that continue today, Lettomanoppello has held its own. It is one of the few mountain towns that is maintaining rather than losing population. New housing continues to be built, and restoration and beautification of the town’s historic center continue, as does preservation of the town’s traditions. Lettomanoppello remains a 'bella paese' of which her far-flung descendents can be proud.

Lu Lette Surnames | La Rocca Surnames | Maps | Family Nicknames

Organizations & Events | Scrapbook | Genealogy Help | Links

Sign Our Guestbook | Home | View Our Guestbook

*DOWNLOAD LU LETTE AND LA ROCCA SONGS*

*DIALECT VERSE ABOUT A LETTESE AND A ROCCOLANO*

*MARIA DI COSTANTINOPOLI LYRICS & LINK TO SONG DOWNLOAD*